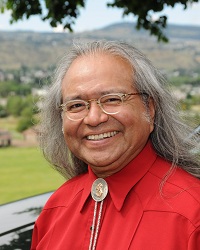

C.T. (Manny) Jules

Chief Commissioner C.T. (Manny) Jules of the First Nations Tax Commission and former Chief of Tk’emlúps te Secwepemc has been a tireless advocate for advancing First Nation jurisdiction. Throughout his career he has been outspoken about First Nations’ ownership of their lands and has now turned his attention to providing a new legal basis for Indigenous Land Title Initiative. The following is an interview with C.T. (Manny) Jules about the Indigenous Land Title Initiative.

Clearing the Path (CTP): In 1988, you led an historic amendment to the Indian Act making it possible for First Nations to assume tax jurisdiction and in 2005 you led an initiative to create the FSMA. You are now leading ILTI. Can you explain why you are leading this initiative?

Ten years ago the Nisga’a signed a treaty which created the concept of Nisga’a lands that would remain so no matter who resided on these lands. The property ownership concept is inspired by the work of the Nisga’a Nation. Because the Nisga’a secured permanent ownership they created their own land title system. In November 2009, the world changed – the Nisga’a issued fee simple title to their members on a portion of their lands.

This creation of title instantly provided security, home equity, wealth and business opportunities for their members.

I believe the Nisga’a option should be available for any First Nation that so chooses. I believe that this can be accomplished by mirroring their excellent work. It will require, however, federal legislation and possible provincial agreement or even legislation. That is why I am seeking support for this initiative.

CTP: Why is there a need to deal with property ownership?

I am supporting this initiative for a number of reasons:

We have land but it is undervalued. This initiative will allow us to provide our members with the ability to own their property. This will create wealth and opportunities for individuals. It will help our youth realize their potential and it will bring us into the market economy. First Nation property ownership will formally bring our governments into the Canadian federation by recognizing our underlying title and allowing us access to the same 21st century property rights as other Canadians.

The Indian Act reserve system substantially reduces land value and promotes low value land use. It prevents us from accessing the equity in our lands, raises our costs of doing business and discourages investment. I know from experience how hard it is to build an economy on reserve land. In Kamloops, we have to be able to compete for business with other governments but our form of land tenure holds us back. This approach to land ownership will allow us to obtain the full value and benefit of our lands by attracting investment. We need to make maximum use of the current expansion of the reserve land base that is taking place through the settlement of land claims and treaty land entitlements.

In 1968 my dad, Chief Clarence Jules, told the government that to be successful we need to be able to do land transactions “at the speed of business”. Here we are forty years later and we still haven’t dealt with the issue. This approach will replace outdated and insufficient band council powers over reserve land under the Indian Act with new law making powers so that we will be enabled to effectively govern, manage and control development of our reserve lands, regardless of who holds fee simple title.

CTP: How does this mesh with the work of the First Nations Tax Commission?

Property ownership is central to economic development for First Nations. I have been working on the issue of property rights certainty for the last 35 years. I was inspired by my father who summed up the plight of our community when he said in 1968 that “we don’t even own our own land.”

Without property rights certainty we cannot compete for the type of business and investment that we need to be part of the economy. Our lack of property rights has meant that our lands have lower market values and we have to spend a great deal of time and money establishing investor certainty. It has meant that our ability to grow our tax bases has been limited.

The purposes of the Tax Commission include growing First Nation economies and expanding their potential to raise local revenues. Creating certainty about individual property ownership and our governments’ jurisdictions through this initiative serves these purposes. My goal in this initiative is to create a Torrens registry system for First Nations that would serve First Nations and significantly enhance the administration, management and enforcement of the First Nation property tax system.

CTP: A growing number of First Nations have achieved economic success within the Indian Act reserve land system, combined with the recent “work around” legislation. Why is this not sufficient?

The “work around” approach you describe isn’t really getting us where we want to be. We need to deal with the issue directly. Yes, there are communities where, because of location, demand overcomes the inadequacy of the system. In some cases, values can be raised but most of our population remains in poverty because they cannot convert their asset (land) into capital (value).

The need for clarity and security of property rights is fundamental. There are a number of reasons why the Indian Act reserve system should not be the sole available foundation for the future of economic development on reserve land. First of all, First Nations wishing to take possession of the title to their reserve lands should be able to do so. First Nations wishing to give individuals fee simple title to their own homes and real property should be able to do so.

Second, the current lack of private property rights promotes an extraordinary dependence on Band Council management and entrepreneurship to develop community assets. Private property rights, on the other hand, support individual entrepreneurship, broadening the base of economic activity and enabling individuals to make an end to their own poverty without depending on the Band Council. There can be no long term solution to the housing problem on reserves without the use of private home ownership to facilitate financing and the development of personal home equity.

Third, we are faced with building an economy that is dependent on leasehold tenure. Few high quality large scale developments are being built on the basis of relatively short term leases (less than 50 years). Long term tenure is essential when significant investments are being made. Leases complicate acquisition of interests in land as well as financing. Banks and other lenders require legal review of documents, which substantially raises transaction costs and, in their minds, risks . This convoluted approach to securing tenure greatly limits investment. And, even after a lease is signed, it is complex to manage with potential future conflicts and challenges, leading to a loss of value. Long term leases raise underlying questions of de facto alienation. Yet, under the current Indian Act system (including recent legislation), leasehold development is the sole option.

CTP: Doesn’t the Indian Lands Registry secure the interest of leasehold tenants and protect the land title for First Nations, their members and investors?

The Indian Lands Registry is a simple repository of information on property interests in reserve lands. It is difficult to access and it is incomplete. It is not underpinned by a well developed legislative base. It provides no legal certainty as to title. There are no priorities of interests allowed for. Developers use the Registry at their own risk. Persons involved in transactions relying on the Registry must review all the historical documents in order to get a degree of certainty which, at the end of the day, still has a measure of risk. Compare this with the proposal where a simple search of the registered title would be all that is required to obtain absolute certainty that title is clear. First Nation developments face the highest transaction costs in the country. Despite the benefits of recent legislative reforms, the costs of doing business on reserve land remain many times higher than off reserve.

Replacing the Indian Lands Registry is a major step to addressing this disparity. These costs are substantially reduced by this initiative for several reasons: Torrens title systems are easier to search and much more secure; First Nation government charges and other liens and interests would be identifiable; a First Nation Torrens system can be easily linked to real estate and tax assessment data bases, making it much easier to establish property values; and it is much easier to negotiate financing based on fee simple title, clarity of seizure procedures, and linkage with other related legislation.

Consider that it takes an average of 1 to 2 days for registration of a mortgage in BC compared to 180 days to complete an equivalent registration under the Indian Lands Registry. A recent study found 23 points of transaction costs which would be reduced by a shift to this proposal.

CTP: Some will say that despite all its flaws, the Indian Act reserve system has preserved a land base for First Nation communities. By permitting individual ownership and even the possibility of sale of parcels of reserve land to non-First Nation parties, will ILTI not lead, inevitably, to the erosion of the reserve land base? What do you say to this view?

I am not advocating the erosion of First Nations jurisdiction over its land. I am talking about strengthening our title by giving First Nations the right to own their own land. This is a critical question and I want to take the time to go through this so there is no misunderstanding:

As a result of this proposal we would maintain our governance over the land and retain the power to make laws related to the use of our land regardless of who is resident, including the power to tax any interest in the land. Through the exercise of permanent and extensive jurisdiction we will continue to obtain the benefit of the land and the land will continue to serve as the basis for the evolution of our community and culture.

We would address the permanence of reversionary interest in the event that individual reserve land holders, whether First Nation persons or not, die intestate and without heirs, title to that land would revert to the First Nation. Reversionary rights could also be exercised through enforcement of First Nation taxation powers.

First Nations will obtain clearly defined powers of expropriation for public purposes as is common to all other governments in Canada. The courts will be available to ensure that expropriation powers are used properly.

Similar protections in democratic process terms would be used as are used today to protect Indian Act reserve land. Before First Nations could use this proposal the consent of a majority of members would also be required.

First Nations would also need to have the option of establishing special protections of their own design, such as setting aside certain lands to remain inalienable, or limiting the sale of certain lands to First Nation members, etc.

CTP: How does the ILTI system of land tenure compare with leasehold tenure, certificates of possession and the impact of the loss of entitlement to heirs?

When we look at leasehold transfers there are many long term leasehold developments

on reserve land today, such as major commercial, industrial and residential developments. In substance these represent a transfer of reserve land into non-First Nation hands. The benefit of the use of the lands flows to our communities through the lease (often paid up-front), through property taxation and, in some cases, through land management authority. In other words, the risk of erosion of the reserve land base already exists and is considered to be acceptable due to the ongoing indirect benefits from the land that continue to flow to the First Nation.

Certificates of possession create a limited type of private ownership. Much Indian Act reserve land has already been converted from communal ownership to Certificates of Possession (CPs) or similar instruments (there are approx. 50,000 CPs registered). The transition from communal possession to private possession is, therefore, already well advanced. However, under the Indian Act system, the benefits of private possession are severely restricted. Thus, while the community has lost the direct use and benefit of the land and retains only indirect benefits, the individual CP holder has not obtained the full value of the land in his or her possession.

Our future is with our children and I am concerned about the current system which can lead to a loss of entitlements to our heirs. There is a complicated formula for determining legal status as an Indian. As a result of this formula, it is possible, through marriage, for a First Nation member’s heirs to become non-status. In the current system, this means that they could not legally bequeath their certificate of possession to their children. This proposal would address this failing and ensure that our children have access to the same wealth creation cycle that other Canadians take for granted and the long term survival of our communities.

CTP: What are the implications for the existing Indian Lands Registry by creating a new Torrens registry?

ILTI would establish the legal basis for a First Nation Torrens registry system. In the Torrens system, registered title is legally guaranteed, accompanied by an up to date survey, and fraudulent activities are settled through the use of an assurance fund. This new system would permit the migration, over time, of reserve land from the Indian Lands Registry to the new Torrens registry.

CTP: What are the next steps?

I am currently seeking interested First Nation communities and individuals to support this initiative. This is the approach I have used for all the past initiatives I have led.

We are seeking support for the concept. We are combining the support and concept with operational requirements and develop some legislative options. Then we will work with Canada to develop the legislative changes to implement this option for interested communities.

You can read more about our proposal at our ILTI website at www.ilti.ca. I would also be pleased to make presentations to any community that is interested.